Interview with Mr. Bo Bengtson • Interviewed by Anne Tureen

Published in Best in Show Annual 2016

In the trailer for today’s interview posted on the fb page of The Literary Dog, I asked which book might be considered ‘The Bible’ of Canine Literature. I can think of two. The first is the great milestone of all time, John H. Walsh’s Encyclopedic ‘The Dogs of the British Isles’, 1867, written under the pseudonym Stonehenge. This gentleman was passionate about sighthounds, wrote a number of books, and also became the editor of the influential magazine ‘The Field’ whose atricles inspired the creation of the Kennel Club in the UK, that great mother organization reproduced across the world. If reincarnation exists, it would be a reasonable explanation of the force behind Bo Bengtson, a leading Sighthound breeder, top handler, active organizer of events, expert judge, and thankfully, a prolific writer. He shares his amazing knowledge with the rest of us in the journal he founded and still contributes to ‘Dogs in Review’, as well as in his many books including a breed encyclopedia, and the volume ‘Best in Show The World of Show Dogs and Dog Shows’, compressed into just under 650 pages. This work enjoys complete pre-eminence in coverage of all professional aspects of the dog world: the breed standards, judges, handlers, breeders, and the history of shows in the USA and around the world just to list a few of the subjects covered in this masterly work. Mr. Bengtson is uniquely qualified to write on all of these subjects and more, since he has been active in dogs since his youth in native Sweden where he revolutionized his breed, and later distinguished himself in all aspects of showing in the USA. I was honored to say the least when he kindly agreed to speak about his life and work.

BIS: You have achieved so much in the disciplines of breeding, showing and judging, did you get an early start?

B.B.: I was born in Sweden and was animal-crazy from the start. We had a Cocker and a Dachshund when I was a kid, and when I was 14 years old I started going to dog shows. I knew right away that this was going to be my life’s interest — I’ve always said that dog shows at their best are like a combination of circus, zoo and high drama … and if I hadn’t become immersed in dog shows I’m sure I would have ended up being involved in any one of those. (I did try to run away with a circus when I was a child, and later on I studied drama and theater history at university.)

BIS: Were Whippets always your main interest?

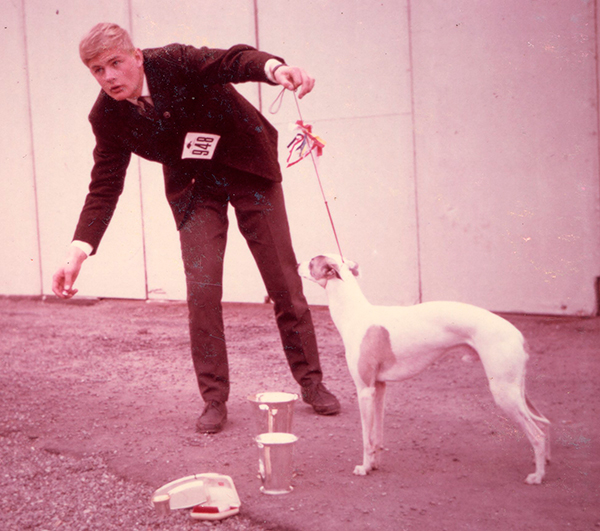

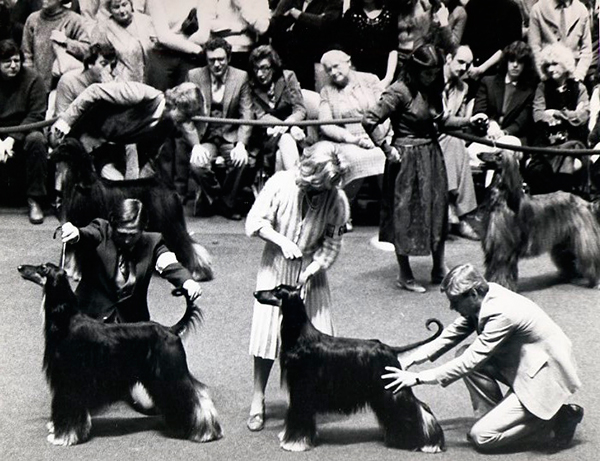

B.B.: My parents allowed my sister and me to get an Afghan Hound in 1959 — not the most practical breed for a couple of kids. We loved her, I showed her to her champion title and some Breed wins, and later we bred the first Bohem champions out of her. I was working in an Afghan Hound kennel in England in 1961 when I met some Whippets that were so wonderful that I knew this would be “my” breed. I have had Whippets for 55 years now… I was lucky to get involved with the Laguna kennel, which was then the most influential in England (or anywhere, for that matter), worked there for a couple of summers and got my first dogs from them. In 1963, when I was 18 years old, I won BIS at the big international show in Stockholm with Int. Ch. Laguna Locomite, and my Int. Ch. Laguna Leader was also a BIS winner and a great sire. Later I imported several dogs from other kennels in England, of which Int. & Eng. Ch. Fleeting Flamboyant was probably the most famous.

I didn’t breed much because I could only have a couple of dogs at home, but those English stud dogs were used by other breeders and helped improve Whippets in Scandinavia . From the few litters that I bred came some really influential Bohem champions. The Swedish Kennel Club awarded me their Hamilton plaque for “excellence in breeding” in the early 1980s.

Also in the 1960s I got involved in Greyhounds. In partnership with Göran Bodegård, now an international FCI all-breeds judge, I bred a litter that included the influential Int. Ch. Guld, who is behind pretty much all top Greyhounds in Scandinavia, and in much of the rest of the world also. In 1976 I showed her daughter Int. & Eng. Ch. Gulds Black & White Lady to Res. BIS at the international Stockholm show from the veteran class. Her daughter Int. Ch. Piruett, bred by Göran and myself, was also BIS at this show. Lady was the first foreign-bred Greyhound to become a champion in the U.K.

BIS: So we find young Bo active both in Sweden and the UK , already on the international scene as a teenager which was uncommon at that time, what was your next step?

B.B.: In 1980 I moved first to Australia, then to California and have lived here ever since. I still have Whippets who descend nine or ten generations down from those old English dogs in Sweden, but I almost never bred more than a litter per year. I hardly breed at all anymore and only have two spayed veteran bitches at home. Nevertheless, there have been about 120 Bohem Whippet champions in many countries over the years, plus about 15 Greyhounds and those Afghan hound champions long ago. Even though I live in America, Whippets I’ve bred have taken several FCI World Winner titles, and more are sired by dogs I sent abroad.

BIS: Would you say you were always a writer or did that devolp with maturity?

B.B.: As a teenager I sent a couple of show reports from England to the Sight hound Club magazine in Sweden. They printed them and that encouraged me to send a few short items to the Swedish KC magazine, Hundsport. I was thrilled when they actually PAID me for this — I somehow hadn’t realized you could make money from writing! Eventually Hundsport asked me to take over all their show reporting; I wrote a lot for them in the 1960s and ‘70s and have continued to do so even after moving to America. I remember starting Hundsport’s annual Top Dog competition in 1965 or ‘66 — there was nothing like that in those days in Sweden nor in most other European countries.

BIS: So journalism was something that has accompanied you for much of your life, how did you begin writing books?

B.B.: Gradually I started writing more, first about dogs in general and then all kinds of pets in a couple of the big daily newspapers, but I realized pretty soon that I didn’t want to become a regular journalist: Most of the older journalists I met were more or less alcoholic, bitter and cynical — even the successful ones! I wrote my first dog book in 1966; it was just a pet-type “Family Dog” book, but it was translated into at least a few different languages. Last year someone in Norway sent me her nearly 50-year old copy of that book, apologizing for the scribbles that her then 5-year old son had made in it. It’s a little disconcerting to realize that this kid must now be well past middle age!

In the 1970s I wrote a couple of other books, including an encyclopedia of dog breeds for a Swedish publisher. I didn’t think it was very good, so waived all rights to it for a fairly small sum. A few years later that book was sold to an international publisher, translated into many different languages and sold more than 500,000 copies worldwide. (I remember seeing it in a bookstore when I was judging in Rio de Janeiro in the 1980s.) If I had gotten royalties I would have had a very nice income from that book for years …

In the late 1970s a British publisher asked if I’d like to write a Whippet breed book. It was a lot of work, but I learned a great deal about breed history and doing research. I’ll never forget going into the famous Foyles Bookshop at Charing Cross Road in London — the world’s biggest book store at the time — and seeing my book on the shelf … That first edition has been revised and expanded twice: the most recent book, “The Whippet – An Authoritative Look at the Breed’s Past, Present and Future” was published in California in 2010. It’s 350 oversize pages with plenty of color photos; it’s sold out now, but they keep telling me they will be printing copies “on demand” in the future.

BIS: Writing and publishing is something many people in the dog world simply cannot find time for regardless of their qualifications. Organizing your own magazine must have been a monumental undertaking, how did that develop, and what was the impact of this project on your life? ?

B.B.: It didn’t really occur to me that writing about dogs could be a real profession until I moved to the U.S. and was offered a partnership in a small publishing company that Paul Lepiane owned. We’ve been partners in life and work now for 35 years. Paul started The Afghan Hound Review, one of the first really big, glossy breed magazines in the 1970s, when he was just out of school. When he also began to publish Poodle Variety a couple of years later things got too big for him, and that’s when I entered the picture. Then I started Sighthound Review in 1984, we took over a Setter magazine for a while, and in 1997 we began to publish Dogs in Review, which soon became huge and very popular worldwide: In the early 2000s we printed several issues that were more than 500 or 600 pages. I’m not sure how we managed to produce a big, monthly all-breed magazine and several bi-monthly specialist magazines from our at-home office with a very small staff … but somehow we did.

Gradually we’ve sold off most of the magazines since the early 2000s. Dogs in Review is now owned by a large company in Los Angeles, but I still write for them. Paul still publishes Poodle Variety, and after selling Sighthound Review many years ago I bought it back fairly recently. I’m having a great time writing, editing and publishing it all on my own — it’s a perfect retirement spot!

BIS: I’m convinced that Providence has awarded you more than the 24 hours in a day that the rest of us are allotted, because apart from showing and breeding and running a magazine (and dashing off a book or two in your spare time) you were earning your credentials as a judge.

B.B.: I started judging in Sweden and England in the 1960s, but I didn’t become an approved FCI judge until 1976. In 1977 I judged nearly 200 entries at the American Whippet Club specialty in Santa Barbara and two years later a similar number at the American Saluki Association’s show there. Those were fantastic experiences, the best any judge could have, but it probably also gave me the wrong idea about what to expect from most judging assignments. I was also lucky enough to judge at Crufts, Westminster, several FCI World Shows and in many different countries around the world in the late 1970s/early ‘80s.

While I was still living in Sweden I was approved by FCI for more breeds than I had asked for, but mostly I had to give up on my judging career after moving here. It’s impossible to judge AKC dog shows and publish dog magazines simultaneously; I don’t know why it’s different in the U.S. than in other countries, but it is. I have judged some big specialties and all-breed shows in the U.S. during the time when I was not working as a publisher, but mostly I have judged abroad, at FCI shows in Europe, England, Australia, Russia, China, etc. I’m currently approved for breeds in 7 of the 10 FCI groups and have judged BIS a few times in Europe, Scandinavia, Russia and Mexico.

When I was young I didn’t think there could be anything greater than becoming an all-breeds judge, but these days I enjoy specialty shows more than anything else. It’s much more interesting to judge a large entry of one of your favorite breeds than judging lots of breeds with smaller entries.

I love traveling; everybody else complains about it, but I have no problem with airports or flyng. However, I don’t want to be away from home, so I don’t judge that much these days. I always like to go back to Sweden and visit, and in 2016 I have a couple of assignments in England that I look forward to — the Whippet Club show and later Best in Show at their Hound Association championship show. But now, for the most part, I prefer to stay home!

BIS: Do you still enjoy showing?

B.B.: I haven’t shown a dog for months … It’s much more interesting to sit at ringside and watch. This week we’ll go to Palm Springs with a few dogs for a specialty show. There’s a new puppy that I co-own and a few veterans, but I wish some young kid would handle the dogs — I don’t enjoy showing the dogs myself that much.

There are not a lot of shows in the U.S. that are worth going to — I’m actually envious of those who show in England or Europe. Other than the specialty shows here in California there’s mostly Palm Springs in January, which is beautiful, and Santa Barbara in August, which is always fun and very international, and then Del Valle in northern California in October. The distances here are enormous; people from Europe tend to forget that — when I go to Westminster it takes almost as long to fly in from California as it does from Europe. I’m a big supporter of Morris & Essex, but the show is held only once every five years, and that’s also back East.

The American Whippet Club’s national specialty will be held in California in April this year, and I look forward to that. The national specialties we have in the U.S. are easily the best dog shows of that kind anywhere! The Whippet national will last a whole week and I expect we’ll get something like 500 Whippets entered. Everyone stays at a hotel with the dogs and there’s so much going on you’re exhausted by the end of it … but a good national specialty is everything that dog shows should be — but very seldom are.

BIS: How did you come to write the Best in Show book? This is a work of unparallelled breadth, dating from the pre-history of shows and providing detailed information concerning every aspect of the dog world and showing. So much information, both historical, anecdotal and plain factual (wins and statistics), is packed into the text, and I wondered how you were able to gather so much information together.

B.B.: It seemed to me for a long time that there must be a place for a comprehensive overview and history of the world of purebred dogs. None had ever been published, as far as I knew. I wanted this book to be worldwide in scope and to cover the entire period that there has been a “dog fancy” in the modern sense, from the beginning of dog shows in England in the mid-1800s to the early 2000s. Most sports and hobby activities have some sort of reference work where you can look up details of past activities and major events, but there just wasn’t one to be found about the dog sport.

It was really difficult to convince a publisher that this was something that realistically could be done, and that it would be a good book. Most people felt it was a far-fetched idea, at least if you wanted it to be as ambitious as I did. I wrote a book proposal for a publisher in late 2004, finally signed a contract in May 2005 and then worked on the manuscript and photos for more than two years. I couldn’t spend all my time on it, of course, since I had to keep my day job: You certainly don’t get rich from writing this kind of book! Half-way through 2007 they were ready for me to start working on proof-reading the manuscript. The finished book was introduced at the AKC/Eukanuba show in Long Beach in December 2007; the official publication date was 2008.

BIS: How much of this information was researched by you from primary sources and how much was culled from other texts?

B.B.: If you mean how much information I could copy from other books of this kind the answer is: pretty much nothing, since I found no similar book that had ever been published before. But of course I quoted from original sources a lot, both from old books and magazines that I had collected. One non-doggy book that turned out to be very important was Henry Mayhew’s wonderfully detailed “London Labour and the London Poor” from the 1840s; it told me more about the beginning of the dog fancy than any other book. But I realized I had to go back much further in time to show that people have admired beautiful dogs of good breeding for as long as there has been a written tradition, or even longer — all the way back to the Odyssey, where there is a reference to dogs being kept for status and “show”… The Greek philosopher and historian Arrian wrote a very affectionate treatise on his beautiful Greyhound in the second century A.D. – the dog even shared his bed! Later on there was Dame Juliana Berner’s famous “breed standard,” again of a Greyhound, and lots of various dog breeds are mentioned by both Chaucer and Shakespeare. I found an illustration of a really elaborate kennel building in France from the 1300s that we were able to print in the book. There is a portrait of a pair of really beautiful Salukis painted in China as early as in the 1400s, and there are those famous “Ten Prized Dogs” paintings from the 1700s. Records exist that tell of Louis XIV giving beautiful little toy spaniels — early Papillons — as a farewell gift to his discarded mistresses, etc. etc.

One of the things I regret is that we weren’t able to give enough space in the book to one of the great early dog paintings, “The Dog Market,” completed in 1677 by the Dutch-born artist Abraham Hondius, who lived in England. The original was owned by Walter Goodman, the famous Skye Terrier breeder and judge who has died since, and although he was kind enough to let us use a high-quality print, it was so late in the publishing process at that time that we were only able to squeeze it in on less than half a page … It ought to have occupied a 2-page spread! It’s an amazing painting and shows clearly that the concept of separate breeds existed long before we had dog shows.

Finding things like that made the research a lot more colorful and put the whole concept of the dog fancy and “breeds” as we know them into perspective. And of course I went back to the early kennel club records in both England and the U.S. a lot. Fortunately I was getting good help from the Kennel Club librarian in the U.K. and spent a lot of time in the AKC library in New York, going through old issues of The AKC Gazette.

BIS: So there is plenty of travel going on, as well as reaching out to the various organizations that keep archives of shows and show history. Your volume is also a visual reference book, there so many pictures of the dogs and people that made the history of this sport.

B.B.: It didn’t hurt that I have a magpie’s instinct of saving anything related to dog shows, or that I had worked on the international show coverage for Dogs in Review for many years. I have a garage full of old magazines going back to the early 1900s with tons of newspaper clippings, photographs and books. We inherited the photo archives from Kennel Review when they folded in the 1990s, which added to our already large photo collection. (I have no idea how many photos we have, certainly more than 10,000 old print photographs — and of course today’s images are almost all digital. The print photos are in folders sorted by breed in a large file cabinet.)

Especially Desiree Scott and Simon Parsons at Dog World in England helped me get information from the early big shows over there, and I compiled results from AKC shows since Best in Show was first made into an official award in 1925. It was more difficult getting records from other countries, but it helped that I had traveled a lot and had contacts in many places, so it was possible to write some kind of dog show history from most parts of the world. Eastern Europe and Russia didn’t have much known dog history before the fall of the

Soviet Union (although there were, in fact, imperial dog shows for Borzoi in Moscow before the Russian Revolution), and Asia has become a big presence on the world scene in recent years. I wish I had been able to write much more about those countries, but it was difficult to get reliable, first-hand information.

BIS: According to Wikipedia, the very first photograph was taken in 1827, but not until about 1900 was photography reasonably available to a large amount of people. It is interesting that the very first photographic sequence (1878) was of a galloping horse, were dogs also an object of interest? Are there many photographs extant of dogs and dog shows?

B.B.: Photographs were a huge problem — not that I didn’t have enough, but the opposite. Sorting through them and deciding what to use was a big undertaking. There were supposed to be “only” 500 photos in the book — we ended up using about 750 illustrations in a 656-page book, but it was still difficult to narrow them down. I remember hiring an assistant who helped spread out thousands of photos on the office floor and putting them in piles for potential use by breed, by year and by geographical location. It was almost impossible to get photos of all the most famous dogs that were flattering of the dog (and the people in the pictures!) and also interesting for a regular reader — plus of course the photos had to be of good technical quality, and we also had to deal with copyrights … I’m not sure how we managed. Fortunately a lot of the active dog show photographers around the world were very helpful and supportive.

Several times I was close to giving up: perhaps it really was impossible to complete a book like this one. Now the division into chapters looks pretty straightforward, but we were working without a model. (I had written a Swedish book about dog shows and show dogs a few years earlier, but it was much smaller and easier to complete.) I had a wonderful, patient editor who kept me sane, but by the time we got to proof-reading I was pretty frazzled … It was a huge relief to finally see the actual, printed book at the AKC/Eukanuba show. They did a beautiful job producing it, and a lot of dog people I respect were very enthusiastic about it. For several years afterward it would happen that even people I didn’t know came up to me at dog shows in various parts of the world and told me they kept the book permanently on their coffee table or nightstand … The reviews were wonderful and the book got a lot of awards. I was particularly proud that it got the Independent Book Publishers’ Benjamin Franklin award for Best Reference/Directory 2009, with a book about child rearing and one on world history as runners-up. I don’t think any other dog book has done that!

BIS: You include many notes on the women who were part of this sport, in fact the role of women seems to be nearly parallel to that of men in this sport from the very beginning. Do you agree?

B.B.: I couldn’t agree less! If Florence Nagle could have heard you say that you would have gotten a lecture in how men kept all the power in the dog world, as everywhere else, to themselves as long as they could! Mrs. Nagle fought long and hard for women to be allowed to become members of The Kennel Club (UK), but that didn’t happen until 1978 — more than ten years after she had succeeded in getting the Jockey Club to award trainer’s licenses to women. Sure, women were sometimes asked to judge at Crufts and Westminster early on, but not nearly as often as men. It was basically a man’s world, in dogs as in everything else — although that didn’t stop a few wealthy and strong-willed women from being successful exhibitors and breeders. I’d love to have met Mrs. Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge, who had the huge Giralda kennels in New Jersey and financed the fantastic Morris & Essex Kennel Club show, the biggest in the world in the late 1930s with over 4,500 dogs … or Mrs. Quintin Dick, later Lorna, Countess Howe, who won Best in Show at Crufts three times with her black Labradors around the same time. But they were the exception, not the rule, and if they had not had the positions they had, from inherited wealth or prestigious marriage, there’s no way they could have achieved what they did.

Countess Howe was in fact supposed to come over from England and judge Best in Show at Westminster, but she never did — I’d love to know what happened. (I remember Joe Braddon telling me that her Banchory dogs were not that great, but of course he competed with them …)

Things have improved a lot in recent years, but I just checked the websites, which I think are current, and as of January 2016 there were 12 men and one single woman on the Board of the American Kennel Club. Of the 24 directors of the General Committee of the Kennel Club (UK), 18 were men and 6 women. And there has STILL never been a woman chairman of the American Kennel Club, the Kennel Club (UK) or of the FCI…

BIS: Between your book and all of the writing done in your magazine and other formats, there is really nothing left to say about dogs and showing, or is there?

B.B.: There are still so many things to write about dogs that there is never space enough… Not only is there so much happening in the show rings and kennel clubs around the world that you’re never short of material, but the horizons for dog shows keep expanding all the time. When I grew up in Sweden in the 1950s and ‘60s everyone knew there were big dog shows in England, and maybe we had heard a little about German Shepherds and Boxers from Germany, but that was it. Then we learned there were big dog shows in southern Europe, in Australia, the U.S. and Canada… — I remember Hans Lehtinen coming back from Sydney in the mid-1970s and telling us about all the beautiful Afghan Hounds he had judged there. We were flabbergasted — nobody knew anything about dog shows in Australia then! Just a few years later I went to live in Sydney for a year, and I’ve been back judging many times. South America has some of the best dogs and handlers in the world, but we didn’t know that until a couple of decades or so ago. Then things started to happen in Japan and some of the other Asian countries, and Russia became a serious player in dogs, as well as Eastern Europe, and now the FCI is planning to hold a World Show in China, which is of course very controversial. Last year I did an interview with FCI president Rafael de Santiago for Dogs in Review, and he comes from Puerto Rico. There’s no way anyone could have imagined all this a few decades ago when I started in dogs.

In the past I was probably ahead of most people in learning about dogs in foreign countries, but now I’m way behind. Things are happening so quickly. Most recently I got an article for Sighthound Review about dog shows in Egypt! You wouldn’t think a country with a predominantly Muslim population could have dog shows, but they do. It seems almost to be one of the first things people want to get involved in, once they reach a certain middle-class level of comfort: to gather around dogs in a sort of friendly and generally peaceful competition…

BIS: What does the future of literature regarding dogs and showing look like to you?

B.B.: I don’t know about books. I’m sure people will still be reading hundreds of years from now, but I don’t know in what form. Personally, I want a book or magazine that I can touch, feel and smell, so I can turn the pages, but that may change. I am pretty sure there’s a future for print publications, though, but they will have a very different purpose than they have now. It’s so easy to get news fast that the value of print publications won’t be to bring news but to sort through it, decide what’s important and needs to be saved, and to analyze and comment on the news so it makes sense to people.

Facebook is a potentially great medium that seems to be largely wasted on gossip and trivia so far. I don’t use it much, but I love email, because you can reach almost anyone you want anywhere in the world at any time, day or night, and they can respond whenever they want. And nothing beats the Internet for quick information: I Google non-stop every day, and although I know Wikipedia isn’t always totally reliable it’s a fantastic source of information.

BIS: What is the meaning, in your opinion, of being Top Dog today? Is it the equivalent of most expensive dog, or is it really an indication of supreme quality in terms of showmanship and stock selection?

B.B.: Of course it isn’t, but what other way of measuring success do we have? I’m not sure it’s possible to produce a Top Dog point system that’s totally fair and will satisfy everyone. What’s more important, Best of Breed wins or Best in Show wins? Is it more impressive to win ten BIS at shows with 1,000 dogs each, or two BIS over 5,000 dogs? I just wish there could be a little more sophistication than we currently have in the U.S., where pretty much all point systems are based on who defeats the greatest number of competitors over a calendar year. If you win BIS you get points for all the dogs competing at that show except one (since you don’t defeat yourself), and if you place Group 4th you get points for all the dogs in that Group at the show except the first four placed in the Group. The result, of course, is that to be No. 1 you need to show as much as possible, so you have a chance to add up as many points as possible. The top dogs in the U.S. are shown at least 150-200 times per year, which is really expensive, exhausting for both the dog and the handler, and of course also keeps any dogs that don’t have a full-time, well-financed handler out of the top rankings, regardless of how good they are.

In addition to the all-breed point systems there is also the “Breed” system, which is based only on how many dogs are defeated by going Best of Breed. Usually there is a small number of dogs that are shown so often that others can’t expect to be among the top few unless they also plan a full-time campaign all year. I always feel that if a dog is shown perhaps one or two weekends a month — maybe 25-50 times a year— it should at least qualify among the top 20 of its breed if it’s a good dog. For most breeds, qualifying for the “Top 20” competitions that are often held at the national specialties is really the best guarantee for a dog’s ability to win in the U.S.

Of course this doesn’t mean that the No. 1 dogs aren’t good. Nobody would spend all the money, time and work involved in campaigning a dog heavily unless it’s a really good dog! There are professional handlers and experienced breeders who make sure of that. But there are always a number of other good dogs that can’t get near the top because they are not shown as often as necessary.

It would be great if it were possible to come up with a loaded system, so e.g. only the best 25 or 50 results of the year were included, or only wins at the biggest show counted … but regardless of what you do it’s not going to make everyone happy.

BIS: You point out in your book that the dog show circuit existed earlier and to a greater extent than is commonly believed, even without highways or airlines. Dog people just love showing! What other parts of your research were surprising to you?

B.B.: Yes, there were “circuits” in the U.S., with several dog shows held near each other even in the past — most people don’t know that. They could go on for a week or even longer. The big difference was that there were less than 150 AKC all-breed shows per year in the mid-1940s; by the early ‘70s that had increased to nearly 600, and in 1985 there were more than 1,000 AKC all-breed shows in a year for the first time. Now we seem to have settled around 1,500 AKC all-breed shows annually, none of which are particularly big by international standards: the average is less than 800 dogs, and few have as many as 4,000 dogs entered. Everyone agrees that’s way too many dog shows, but nobody seems to know how to change it.

What surprised me when writing the book really was how little dog people have changed. Dog show people were as crazy then as they are now! There was a Pointer in the 1870s who was shown at least 60 times, maybe even more, in both Great Britain and Germany … Can you imagine how difficult that must have been, before the advent of cars, before telephones? How did they even find out where the shows were? How did they make their entries? How did they get to the shows? The fact that people from England on occasion showed dogs in America at a time when it took weeks just getting from one country to another is really amazing. I remember reading that an exhibitor from Japan was showing at Westminster — or maybe it was Morris & Essex — in the 1930s… I’ll have to find that article.

Otherwise, I guess what was interesting to me was to realize how old the fascination with different dog breeds is — it’s been going on for hundreds of years, even thousands, before there were dog shows. Also how universal it is: It all started in England, of course, but there really is a world-wide trend that people want to get together in organized dog shows and form a dog fancy. Whenever there’s a solid middle class, not necessarily wealthy but

obviously with time and money to devote to something more than just surviving for the day, then this is where a dog fancy will be forming …

BIS: After sifting through all those photos, would you say most breeds have changed a lot over the years?

B.B.: It sure looks like it, but you really cannot judge from old photos. Some of the dogs from the past look so different that it’s difficult to imagine how they could win so much, but that’s looking at them with modern eyes. Many of the great movie stars of old, silent movies were famous for their beauty in their own time, and they don’t look so hot to us today either. Certainly human features don’t change that much over a few generations, so I think it’s primarily that what we select as objects of admiration is different now and then. If you add changes in presentation, grooming, handling, stacking and of course photography, it’s no wonder that some of the old winners look really odd to us.

On occasion there are dogs — or photos — that transcend the years. For instance, the Great Dane Ch. Etfa von der Saalburg from the 1920s looks like she could win anything today … and there are others, but frankly you see more in old film or videos. I remember seeing a glimpse of an Old English Sheepdog that was used for herding in England in the 1930s on TV, and that dog looked fantastic. There were a few Borzoi in a Russian film that must have been from before 1917 who looked wonderful. I found a clip from Whippet racing in England in 1915 — most of the dogs wouldn’t win today, but there’s a brief shot of a couple of men coming through a gate with their dogs, and one of them is particolor, bigger than the rest and looked like he could have been “the father of the breed.” It gave me goosebumps …

And before we get too smug about our beautiful dogs today, let’s imagine what people will think of them maybe fifty or a hundred years from now. And of course I’m wondering what their dogs would look like to us today if we could see them!

BIS: Several times in each chapter I found myself thinking: ‘Oh, I’d like to read more about that

person.’ Which of the many fascinating figures in the history of dogs would you think merits a full-scale biography?

B.B.: One of the most interesting personalities in dogs, and probably the sharpest mind, that I can think of is Raymond Oppenheimer, who had the Ormandy Bull Terriers in England. He wrote a couple of fantastic books that ought to be compulsory reading for anyone who takes dogs seriously. (“McGuffin & Co.” and “After Bar Sinister” — difficult to get hold of and very expensive but worth every penny!) Obviously he wrote primarily about his own breed, but there’s so much that applies to dogs in general. I only met Mr. Oppenheimer once, but it left an indelible impression: I was invited to lunch with a Swedish Bull Terrier friend at Ormandy long ago, and afterward we were shown all the Ormandy and Souperlative dogs by his friend and kennel manager, Eva Weatherill. It sounds presumptuous if I say I wish I had known him, but just to be able to sit and listen to him talk about dogs would have been fantastic.

There was of course Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge, whom I mentioned earlier. She has probably been profiled more often than any other American dog person. As the wealthiest woman in the U.S. of her time she was able to import all the top dogs she wanted from around the world. (A lot of German Shepherds and a legendary Doberman from Germany, primarily Pointers from England and many other breeds.) She was married to Hartley Dodge, of Remington Arms, and their son, Marcellus, was killed in a car accident in France when he was still quite young. I would love to know what she actually thought of the dogs she showed and bred. What were her thoughts on the American Kennel Club when they, according to some reports, scuttled her plans for the wonderful Morris & Essex KC shows in 1958, leaving it as lost for many years until a rebirth long after her death in 2000. (The recent 2015 show was a big success!)

In England, of course, Countess Howe would be a similarly august subject of interest. There’s one other person I’d very much like to meet … or if not meet, at least be able to study and listen to: Lady Wentworth, who is best known for her Crabbet Arabian Horses, but she also bred Toy dogs and wrote a classic book, “Toy Dogs and Their Ancestors.” She sounds like a fascinating person — she certainly knew what she wanted, and how to get it! Of course Florence Nagle would have been interesting to talk to — I missed the opportunity of meeting her when I could have and never saw her Sulhamstead Irish Wolfhounds at home. (Probably that was because I was a great fan of the Eaglescrag Wolfhounds, which were related to Mrs. Nagle’s dogs but very different in type. I showed some Eaglescrag dogs and got dragged into the Sulhamstead/Eaglescrag type controvesy.) And speaking of Mrs. Nagle, I wish I had known Anastasia Noble better: her Ardkinglas Deerhounds are behind pretty much everything in that breed. She was very nice on the occasions that I met her, and she must have led a fascinating life. She was a colorful “natural” breeder of the best and most influential Deerhounds ever.

In my own breed I would give a lot to have a few conversations with Stanley Wilkin and Willie Beara, the two brightest Whippet breeders of the 1930s and ‘40s. Both were gone long before my time, both were extremely talented breeders, and neither wrote down what they thought about the dogs that are way back in all our pedigrees. I would love to know! But of course I was lucky to be able to talk to the breeders who were still around in the late 1950s and early ‘60s, from Charles Douglas Todd to Dorrit McKay, and that’s something I really appreciate.

None of these Whippet people was particularly wealthy, as far as I know, but most of the other people I’ve mentioned were either wealthy or aristocratic or both. The fact is that if you wanted to be really successful in dogs, as in most other things, you needed that kind of background, especially in the past and especially to become well-known outside your own breed. But it’s what you do with your money and influence that matters; there were many who in spite of a privileged background failed to have much of an impact.

Of course money always helps, but I don’t think it’s as necessary today as it used to be. If you’re really talented and determined to succeed I think you can go far, even without tons of money or status.

BIS: What are your feelings about the future of purebred dogs and dog shows?

B.B.: I worry a lot about that, at least in the U.S. There are so many problems facing the dog fancy and we haven’t been very good at dealing with them. Everyone who comes from America to dog shows in Europe is so impressed by the fact that the shows are so big, there are so many owner-handlers and so many YOUNG people at the dog shows! The AKC is trying to get more young people involved, but the way dog shows have developed in the U.S. that’s not going to be easy. We have lots of talented young handlers but not so many young people who are involved in breeding, club work, organizing dog shows, etc.

BIS: Your work has resulted in a series of achievements, I don’t think there is space to list them all, so what remains on your ‘to do’ list? Or, perhaps, there are some things you would like to change?

B.B.: I guess I’m a little disappointed that I haven’t been able to accept the opportunities to judge as much as I want. Probably I would make a pretty decent all-breeds judge: I have had the opportunity to develop a much deeper all-around background in dogs than many in this sport … But you have to choose, you can’t do everything, and to me it was much more important to be able to publish a really good dog magazine than to be an all-breeds judges. Some people at AKC are terrific, want to give me more breeds and ask me to get back to judging, but others at AKC are not so nice …

If there’s one thing I’d still like to do, it would be a dream project to publish a really big, beautiful book — “Sighthounds in Art.” (If it were “Dogs in Art” it would have to be several thick volumes, and I won’t live long enough to finish that!) It’s not going to happen, because it would be too expensive to print and probably impossible to get the copyrights to all the great paintings, but it could be a huge, wonderful book … When I was in St. Petersburg a couple of years ago I saw that wonderful painting at the Hermitage museum of Catherine the Great walking with her Whippet in the park — there are so many paintings like that, and I would have loved to present them all in one place.

Otherwise, I’m just happy to be around and see what happens with dogs in the future. I hope I’ll be able to have at least a couple of Whippets as long as I live. What more can you ask?